Liberalisation of agricultural policies: the case of New Zealand

Partager la page

The Analysis notes present in four pages the essential reflections on a current subject falling within the areas of intervention of the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty. Depending on the numbers, they favor a prospective, strategic or evaluative approach.

Liberalisation of agricultural policies: the case of New Zealand – Analysis n°210

New Zealand’s agricultural policy has undergone major changes over time. This note highlights its role in the country’s agricultural transformations. It shows that although public authorities intervened strongly to encourage the development of family and grassland dairy production, this support declined from the 1950s onwards. The liberalisation of 1984-1985, which affected not just the agricultural sector but the whole of the country’s economy, had a major impact on agricultural dynamics at work.

Introduction

In terms of agricultural policy, New Zealand is almost unique in that, in 1984-1985, the country almost completely dismantled the regulatory mechanisms that had existed in the agricultural sector until then. This situation makes New Zealand a textbook case for studying the consequences of the “liberalisation” of agricultural policies, a term understood here as the reduction of State intervention in this sector.

Several studies have analysed the liberalisation of New Zealand’s agricultural policy, and there are many differences of interpretation. For some, 1985 marked the transition “from one of the most regulated systems in the world at that time to very strong liberalisation”1, with the government choosing to “eliminate all state distortions […] and fully expose the agricultural sector to market forces”.2 Others, without downplaying the importance of the changes made, note that the core of the reform consisted in abolishing direct support, which had only been introduced during the previous decade.3

This note examines the aims and consequences of the 1985 deregulation, focusing on dairy production and placing it in a historical perspective. The first part analyses the tools for regulating the agricultural sector that were gradually put in place, and their role in the emergence of family and grassland dairy production. The second part shows that from the 1950s onwards, New Zealand dairy farmers were exposed to international competition, which conducted them, given the regulations in place at the time, to adopt agro-ecological production methods. The final section describes the reforms introduced in 1985 and their consequences.

State intervention in favor of family and grassland dairy farming (1880-1940)

The end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth were characterised by increasing interventionism on the part of the New Zealand government in agricultural matters. This section describes the tools introduced and highlights their role in agricultural change.

An agriculture initially dominated by large-scale farming (1880)

British colonisation of New Zealand, which began in 1840, was far from complete by 1880, at least on the North Island. By contrast, almost the entire South Island had been farmed since the 1860s.

In 1880, the country’s agriculture was dominated by large, capitalist farms relying on hired workers and owned by wealthy settlers from the English gentry. Their farms, covering tens of thousands of hectares, focused on wool production, possibly combined with cereal growing. The employees of these large estates generally owned small plots of land where they practised self-subsistence farming. At the time, New Zealand’s agrarian society was socially very differentiated and unequal. The 1878 census shows that the 417 farms of more than 2,000 ha, which represented only 1.6% of New Zealand’s farms, accounted for almost 60% of the country’s utilised agricultural area (UAA). At the other end of the spectrum, the 6,000 farms with less than 4 ha, or 23% of production units, shared only 0.2% of the total UAA.

The emergence of family farming with the support of the governments (1880-1920)

The global crisis of overproduction at the end of the 19th century4 had a direct impact on New Zealand. Wool and wheat prices plummeted, leading to the bankruptcy of many large estates. In response, family farming received growing support from public authorities, who saw it as a way of making up for the failure of the capitalist model. This support for family farming reached its peak in 1891, with the arrival in power of a Liberal government openly committed to its cause.

This support took the form of new mechanisms for allocating land for colonisation, mainly on the North Island, that were administrated in order to give priority to farmers with limited resources. On the South Island, the priority was to dismantle the large estates to allow family farmers to settle on smaller plots. To achieve this, the government introduced in 1891 a progressive land tax, the rate of which increased according to the area of land held. Even more radical, the Land for Settlement Act (1894) gave the State the power to seize large estates, expropriate their owners and subdivide them to allow family farmers to settle.

While these measures supported the emergence of family farming, which gradually took hold at the beginning of the 20th century, it would be wrong to assume that they provided general access to agricultural land. A whole fringe of the population (particularly the Maoris and day labourers on the large estates) remained excluded. Another mistake would be to consider that this development is due solely to the policies implemented. In many respects, these policies appear to have supported, rather than initiated, a process that was already underway. Indeed, from the early 1880s, faced with falling farm prices, many large landowners sold their farms, without any need for state intervention. Furthermore, before being supported by the government, family farming was supported by the merchant bourgeoisie (banks, exporters, etc.), who saw it as an effective substitute for large estates and made their capital available to it.5

State intervention in favor of grassland dairy production (1920-1940)

The early 20th century saw a boom in milk production in New Zealand, whose products (butter, cheese) could now be exported by sea. Milk production grew mainly on the North Island, where climate conditions were favourable. In the south, sheep farming and cereal growing continued to predominate.

Dairy systems introduced in 1920 relied on annual forage crops (cabbage, beetroot) for winter feed. These were labour-intensive and limited farmers’ labour productivity. Most agronomists at the time suggested doing away with them and replacing them with long-term multi-species meadows. The persistence and yields of these grasslands would be increased by varietal selection, the use of lime and phosphate fertilisers, and the introduction of rotational grazing. The greater productivity of grasslands should make it possible to substitute hay for annual forage crops in animal feed by mechanising haymaking.

These transformations required investments that the economic context of the 1920s did not allow. Therefore, their implementation required the support of the State. This translated into the negotiation of the Ottawa Agreement (1932), which gave New Zealand agricultural products preferential access to the British market. The government also set up marketing boards to regulate export production. This regulation was strengthened in 1935, when the first Labour government came to power. It introduced guaranteed prices for dairy products, calculated to cover production costs.6 The result was an increase in the price of milk (figure 1). In addition, measures were introduced to facilitate access to inputs (transport subsidies for lime and phosphate fertilisers) and capital (creation of a public agricultural credit bank).7

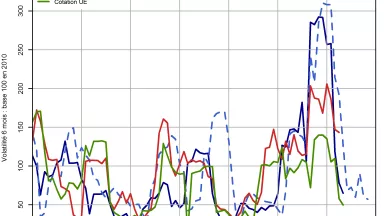

Figure 1. Changes in production volumes and milk prices in New Zealand between 1920 and 1955

Un graphique montre l’évolution des volumes de production et du prix du lait en Nouvelle-Zélande entre 1920 et 1955.

A graph showing the evolution of production volumes and milk prices in New Zealand between 1920 and 1955.

Source: New Zealand Official Yearbook, 1956

This governmental support enabled New Zealand farmers to implement the “grassland revolution”8 from 1935 onwards. The result was an increase in the volumes of butter and cheese produced and exported (a ninefold increase for butter between 1920 and 1940, and a 70% increase for cheese). New Zealand became the UK’s leading supplier of butter, which was then considered as a hub for international dairy products.

Dairy farmers exposed to international competition with little support (1950-1985)

From the 1950s onwards, New Zealand dairy farmers have been increasingly exposed to international competition. Faced with a difficult economic context, they implemented an original agricultural development, focusing on agro-ecology.

Falling milk prices due to subsidised European exports

The implementation of the Common Agricultural Policy from 1957 onwards, and especially 1962, led to an increase in European dairy exports. Subsidised, they created stiff competition with New Zealand exports. Under these conditions, unless it agreed to mobilise substantial budgetary resources, the New Zealand government was unable to maintain the guaranteed price system introduced in 1936. The Dairy Board Act (1961) removed any reference to the cost of production in setting the guaranteed price, and the latter became a only tool for smoothing out international prices and reducing their fluctuations from one year to the next.

The situation became even more complicated in 1973 when the United Kingdom joined the European Common Market. New Zealand then lost its privileged access to the British market, which absorbed 83% of its butter exports and 72% of its cheese exports.9 In this context, milk prices at the farm level plummeted and were divided by four in constant currency between 1950 and 1985 (figure 2).

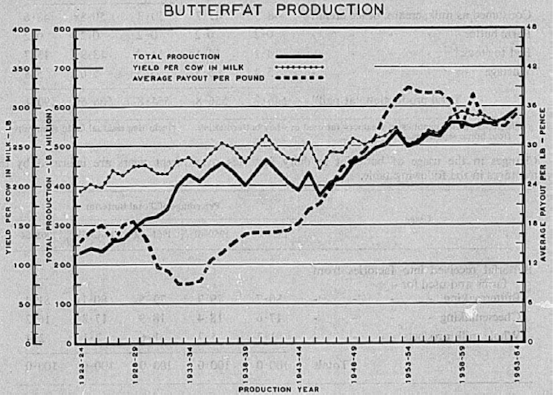

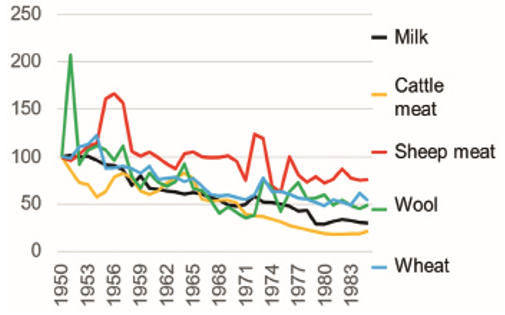

Figure 2. Farmgate prices of main agricultural products, constant currency, base 100 = 1950

A graph shows the evolution of agricultural prices, in constant currency, with a base of 100 in 1950.

Source: FAOStats et Infoshare

At the same time, farmers faced high prices for inputs and equipment. This was the result of the import control introduced in 1937 to maintain the country’s balance of trade. This measure contributed to increase the price of main imported products (nitrogen fertilizers, animal feed, tractors, etc.) by 35 to 55%.10

Introduction of subsidies in the 1970s, from which dairy farmers benefited little

The 1970s were marked by the introduction of direct payments. They aimed to support the agricultural sector, then weakened by the loss of the British market. Numerous direct subsidies were created: support for investments, subsidies for the use of fertilizers and lime, etc. A countercyclical subsidy was also introduced in 1978, the Supplementary Minimum Price (SMP). Producers of milk, meat and wool received payments when the price of their products falls below a floor set annually by the government. The determination of the floor price does not follow precise calculation methods. Retrospectively, it appears that the floor prices for sheep meat and wool were set at levels above international prices, resulting in the payment of compensatory aid about every two years. In contrast, the floor prices for milk seem to have been set at particularly low levels, given that from 1978 to 1985, dairy farmers only received countercyclical aid during the 1978-1979 season.

Generally speaking, and particularly because of the way in which the SMP was administered, the public support for agriculture introduced in the 1970s mainly benefited to sheep farmers. In 1984, it accounted for 90% of their turnover, compared with just 13% for dairy farmers.

In response to this difficult economic context, focus on low-input dairy systems

In most “developed countries”, post-Second World War agricultural modernisation relied on motorisation and enlargement of production units, genetic selection and massive use of inputs to increase yields. It required farmers to have significant investment and cash flow capacity. While North American and European producers have benefited from an economic context favourable to such transformations, due in particular to the agricultural policies implemented on those continents, the same cannot be said for New Zealand dairy farmers, caught between a falling milk price and rising input prices as a result of imports control.

In response, New Zealand dairy farmers turned to highly productive, low-input grazing production systems in phase with on agro-ecological principles.11 Their aim was to increase production without resorting to expensive inputs and equipment, so as to maintain their income despite falling milk prices. In concrete terms, they replaced their multi-species meadows with long-term meadows (15-20 years) made up of English ryegrass (capable of growing in winter in the climatic conditions of the North Island) and white clover (capable of fixing nitrogen from the air to ensure nitrogen fertilisation of the meadow without synthetic fertiliser). The production schedule was adjusted to the growth of the grass: drying off in winter to minimise forage requirements during the low fodder period, calving at the end of winter to take advantage of the peak in grass production in spring, culling and once-a-day milking in summer to compensate for the slower growth of the grass in summer, and so on. The use of electric fencing allowed dynamic rotational grazing, which optimises grass production and its use. These developments led to a considerable increase in farmers’ labour productivity, which rose from around 75,000 kg of milk per worker per year in 1950 to 200,000 kg in 1985. This has been achieved without any significant change in farm size, but with a significant increase in stocking rates.

These changes required very little investment and were therefore accessible to most farmers, at least on the North Island. The reduction in the number of dairy farms (-30% between 1950 and 1985) was smaller than the fall in milk prices (-75% over the same period) would have suggested. In the South, farmers suffer from temperatures that are too cold in winter for them to benefit from any grass growth, which prevents them from implementing the changes described above. Already few in number, their numbers declined rapidly (-70% between 1950 and 1985), to the benefit of sheep and cereal farming, which received greater support from public authorities.

Liberalisation and new approaches to agricultural development (1985-2020)

The liberalisation of New Zealand’s agricultural policy in 1985 is often analysed as the end of agricultural subsidies. However, this was only one facet of a wider deregulation of the country’s economy, whose consequences have been far greater than agricultural subsidies removing.

Virtually complete deregulation of agricultural, economic, monetary and social policies

The deregulation implemented in 1985 was a response to the economic crisis that the country had been experiencing since 1973 and the first oil crisis. This crisis resulted in chronic trade deficit, weak growth, rising unemployment and a deterioration in public finances. The Labour Party, which returned to power in 1984, embarked on a wide-ranging programme of economic reforms (figure 3).

Figure 3. Main measures taken since 1984 to liberalise the New Zealand economy

| Agricultural policy: increasing exports through free allocation of resources | Economic policy : improve capital access and attract foreign capital | Monetary policy : limit Inflation and attract foreign capital | Social policy : reduce the prix of labour |

|

|

|

|

Source : Author

On the agricultural front, the aim was to increase production and exports through free allocation of resources. To achieve this, import control was abolished, giving farmers access to cheap inputs and equipment. The agricultural subsidies introduced in the 1970s were also removed. In addition to the objective of reducing public expenditure, it was felt that the reason why certain types of production needed public support was that they were not sufficiently competitive. Other relatively secondary schemes were also abolished: control of farm structures, support for young farmers, etc.

On the economic front, the changes underway aimed at facilitating access to capital in order to stimulate investment and attract foreign capital. Control on capital flows was lifted, and the financial sector liberalized (elimination of numerous prudential standards). Corporate taxation was also reduced. The tax rate on profits felt from 45% for companies resident in New Zealand and 50% for non-residents in 1984, to 33% regardless of the status of the company in 1985, then 30% in 2008 and 28% in 2011. Finally, conditions imposed on the acquisition of agricultural land by foreign investors were relatively light.

New Zealand’s government also introduced major social reforms, with the aim of reducing the cost of labour: deregulation of the labour market, tougher conditions of access to social benefits to encourage unemployed people to return to work, etc. Finally, the agricultural sector benefited from a very accommodating migration policy, which makes it easier to hire foreign workers. In addition to the fact that these migrant workers generally have limited requirements in terms of pay and working conditions, their conditions of entry and residence in New Zealand place them in an unfavourable bargaining position vis-à-vis their employers.12

A new development model for dairy farming: higher-inputs forage systems and a trend towards financialization

The abolition of agricultural subsidies had no significant effect on the dairy sector, as it never really benefited from them. Furthermore, from 1985 onwards, farmgate milk prices stabilised (1985-2000) and then tended to rise (2000-2020). This was the result of increased demand from Asia and stagnation in European production, linked to the introduction of milk quotas in 1984. At the same time, the end of import controls led to a fall in input prices. Finally, the interest rate, deregulated since 1985, fell. Coupled with a rather lax lending policies from banks (at least until the 2008 financial crisis), it became much easier for dairy farmers to access capital through debt. The economic climate from 1985 onwards was therefore particularly favourable for dairy farmers (figure 4). This led to major changes in production methods, with a switch to higer-inputs forage systems and a trend towards financialization.

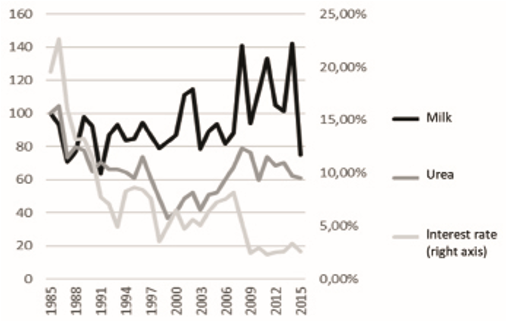

Figure 4. Changes in milk and urea prices (left axis, constant currency, base 100 = 1985) and interest rate (right axis)

A graph shows the evolution of milk and urea prices, on the left axis in constant currency with a base of 100 in 1985, and on the right axis interest rates.

In terms of fodder systems, farmers first turned to synthetic nitrogen fertilisers, the price of which fell by 60% between 1985 and 2000, to extend the grass growing period and build up silage stocks. These were distributed in summer, along with palm kernel cake. From the 2000s onwards, the introduction of silage maize into fodder systems made it possible to increase the energy density of rations and yields per animal. Physical labour productivity in dairy farming can now exceed one million litres of milk per worker per year. All in all, milk production methods are tending to converge with those prevailing in other “developed countries”. This has been accompanied by a significant increase in environmental pressures. By way of illustration, the consumption of nitrogen fertilisers has increased more than 20-fold in the space of forty years, rising from barely 20,000 tonnes of nitrogen equivalent per year in the early 1980s to more than 420,000 tonnes per year in 2022.

From the 1990s onwards, milk production developed strongly on the South Island, thanks to massive investment by capital from outside the agricultural sector. This financialization13 led to the conversion to milk production of former sheep farms, which had been weakened by the withdrawal of the public support on which they depended. Three phases can be distinguished in this financialization process. The first (1990-2000) was driven by wealthy real estate investors who had accumulated a lot of capital in the 1970s and were looking for new investment opportunities. They realised substantial capital gains by buying sheep farms at low prices and selling them a few years later, having made the investments required to convert them to milk production. The second phase (2000-2008) was dominated by investors with more limited resources (self-employed persons, executives, rural entrepreneurs, etc.). For them, the return on investment relies less on the increase in land value than on the income they expected from milk production. The latter increased in the early 2000s, driven by rising prices and falling labour costs. Finally, the last phase (2008-2020) was marked by the arrival of international investors (pension funds, Chinese investors), who took advantage of favourable tax conditions and rather limited restrictions on the acquisition of agricultural land by foreign investors. Actually until 2017, only transactions involving areas larger than ten times the average farm size in the production sector concerned were subject to extensive administrative controls.

The mid-1980s therefore marked a break in the trends at work in the New Zealand dairy sector. The reasons for this are not primarily to be found in the abolition of agricultural subsidies, but rather in the more general measures of economic adopted from 1984-85 onwards.

Conclusion

Agricultural policies played an important role in the development of dairy production in New Zealand. In the early 20th century, government intervention, although not the only driving force behind the changes that took place, was central to the emergence of family dairy production based on grassland systems. These regulations were partly called into question from 1960 onwards, leading dairy farmers to explore original avenues of agricultural development. The deregulation of 1985 led to the adoption of higher-input forage systems and a certain degree of financialisation.

Placed in a long-term historical perspective, the 1985 reforms, which should not be limited to their strictly agricultural dimension, do not mark the transition from a hyper-regulated and protected economic environment to unbridled liberalism. Rather, they reflect a new positioning for New Zealand in global capitalism. These developments have taken place in a particular context, marked by an increase in global demand for dairy products and a shortage of supply. It is likely that the changes in the New Zealand dairy sector would have been different in a less favourable context.

If the economic situation remains favourable, and in particular, if Chinese imports remain buoyant, the changes described above (financialization and higher input forage systems) should continue. New Zealand would then have every chance of retaining its position as the world’s leading exporter of dairy products, a position taken from the European Union in the early 2000s. However, two factors could alter this trend: difficulties in accessing labour, which have been exacerbated by the 2022 immigration reforms, and the strict controls imposed since 2017 on the acquisition of agricultural land by foreign investors.

Mickaël Hugonnet

Centre for Studies and Strategic Foresight

Notes

1. Cassagnou M., Berger C., 2023, « Nouvelle-Zélande : entre plafonnement de la production laitière et contraintes environnementales », Les dossiers économie de l’élevage, n° 543, Institut de l’élevage, https://idele.fr/detail-article/nouvelle-zelande-entre-plafonnement-de-la-production-laitiere-et-contraintes-environnementales

2. Smith W., Montgomery H., 2004, “Revolution or evolution? New Zealand agriculture since 1984”, GeoJournal, vol. 59, n°107-118, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:GEJO.0000019969.38496.82

3. Gouin D.-M., Batailler C., Benson V., 2005, L’adaptation du secteur agricole à l’abolition du soutien de l’État en Nouvelle-Zélande, rapport final, Institut canadien des politiques agro-alimentaires, https://capi-icpa.ca/fr/explorer/ressources/ladaptation-du-secteur-agricole-a-labolition-du-soutien-de-letat-en-nouvelle-zelande/

4. Mazoyer M., Roudart L., 1997, Histoire des agricultures du monde, Seuil.

5. Fairweather J., 1992, “Agrarian Restructuring in New Zealand”, Research Report, n° 213, Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit (AERU), Lincoln University.

6. Martin, S., 1986, Economic aspects of market segmentation without supply control, Lincoln College.

7. Nightingale, T., 2008, “Government and agriculture - Government support and incentives, 1918-1938”, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, URL: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/government-and-agriculture/page-6

8. Smallfield, P., 1970, The Grasslands Revolution in New Zealand, Hodder & Stoughton.

9. New Zealand did, however, manage to obtain duty-free import quotas for butter and cheese, but the volumes involved were small compared with the quantities previously traded.

10. Lattimore, R., 1987, Economic adjustment in New Zealand. A developed country case study of policies and problems, Lincoln University.

11. Hugonnet, M., Devienne, S., 2018, « Systèmes laitiers herbagers en Nouvelle-Zélande : perte d’autonomie et nouvelles logiques de développement agricole », Fourrages, n° 232, https://afpf-asso.fr/article/systemes-laitiers-herbagers-en-nouvelle-zelande-perte-d-autonomie-et-nouvelles-logiques-de-developpement-agricole

12. Kambuta J., Edwards P., Bicknell K., 2024, “Navigating integration challenges: Insights from migrant dairy farm workers in New Zealand”, Journal of Rural Studies, n° 112, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2024.103454

13. M., Boche M., Gédouin M., Magnan A., 2022, Financiarisation de la production agricole : une analyse des enjeux fonciers, Analyse, n° 174, Centre d’études et de prospective, https://agriculture.gouv.fr/financiarisation-de-la-production-agricole-une-analyse-des-enjeux-fonciers-analyse-ndeg-174

Voir aussi

Accords de libre-échange UE/Nouvelle-Zélande et UE/Australie : risques et opportunités pour les filières européennes de ruminants - Analyse n°156

05 novembre 2020CEP | Centre d’études et de prospective

La gestion publique des questions agricoles en Australie - Analyse n° 91

17 juin 2016Enseignement & recherche

La mondialisation par le commerce des produits alimentaires : tendances structurelles et exploration prospective - Analyse n° 102

04 juillet 2017Enseignement & recherche