What futures for the French fruit and vegetable sectors by 2040?

Partager la page

The Analysis Notes present, in four pages, the main points of discussion on a current topic relevant to the areas of activity of the Department of Agriculture, Agri-Food, and Food Sovereignty. Depending on the topic, they take a forward-looking, strategic, or evaluative approach..

France’s self-sufficiency rate in fruit and vegetables is deteriorating over time. In this context, the Ministry of Agriculture, Agrifood and Food Sovereignty commissioned a foresight study on the future of these sectors. Conducted by CERESCO and AgroClimat1, it explores likely development trajectories to 2040. It shows that maintaining production levels will depend on the capacity to adapt to climate change and its consequences: diversification of species and varieties, shifts in production basins, etc. Such changes will affect competitiveness factors in these sectors, and efforts will be needed to better match consumption with production, at national level.

Introduction

The fruit and vegetable sectors (including potatoes) account for 2.3 % of France’s utilised agricultural area and represent over 13 % of farms. They are characterised by varied production models: open-field growing, diversified market gardening, greenhouse cultivation, annual or perennial crops, and produce destined for processing or for the fresh market. This diversity, also reflected in marketing channels, is both a strength and a weakness. It makes it possible to withstand market volatility and to meet the diversity of consumer expectations, which vary with age, social category, lifestyle, etc. Conversely, this diversity increases the difficulties encountered by stakeholders (adapting mechanisation and biocontrol solutions to species and environments, etc.) and disperses their response capacities. These sectors also face structural difficulties, such as declining yields for most cultivated species, and increasing challenges in recruiting permanent or seasonal labour, which is fundamental to the sector. In addition, the necessary adaptation to climate change and the challenges of food sovereignty raise several questions. Which factors or trends could disrupt national and international production and supply chains? What will be the impacts of climate change on the fruit and vegetable production, which is particularly sensitive to weather conditions? How will the sectors be able to adapt? How will food consumption evolve, and with what impacts on the production stage?

In the face of these uncertainties, a foresight study on the future of the fruit and vegetable sectors to 2040 was commissioned by the Ministry of Agriculture, Agrifood and Food Sovereignty. Its findings complement the fruit and vegetable sovereignty plan launched in 20232, and other national initiatives, such as the foresight exercise for the French agri-food industry to 20404 and the study on the potato market4. Conducted by CERESCO and AgroClimat, with support from a working group comprising representatives of the different actors of the value chain, it produced an overall diagnosis, notably based on biogeographical projections for fruit and vegetables in France. Biogeography studies the distribution of species across space. In a context of global warming, it helps anticipate the geographical evolution of cropping zones and changes in the seasonality of cultivated species. Four contrasting scenarios were then developed to help stakeholders prepare for different possible futures.

The final report addresses many topics beyond those presented here, which mainly concern the geographical evolution of fruit and vegetable production as a result of climate change. The first part of this note presents the main lessons from the biogeographical study of fruit and vegetables in France. The four foresight scenarios and their consequences for production are then summarised.

1. Climate change and evolving biogeographies of fruit and vegetables

The study of changes in the geographical distribution of production, carried out by AgroClimat, highlights changes linked to climate, seasonality and species development in the decades ahead. As fruit and vegetable production is particularly sensitive to weather events, the work underlines the adaptations required to maintain economically viable sectors, with differences between the tree-fruit and vegetable sectors.

Modelling the geographical distribution of production

The biogeographical analysis focused on three emblematic tree-crop species (apricots, walnuts and apples). It was performed for the current climate, as well as for the horizons 2040–2060 and 2080–2100, with and without irrigation, and according to different RCP5 climate scenarios defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). It led to the development of maps of the economic production potential by variety (Figure 1 for the Bergeron apricot). This potential is calculated from eight agronomic indicators representing the main constraints on the development of a variety6. For vegetable crops, other biogeographical analyses, based on the GAEZ-FAO7 method adapted by AgroClimat, made it possible to produce maps showing limitations to potential photosynthesis due to climatic, soil-related and socio-economic factors. This second set of maps was produced at species level rather than variety level.

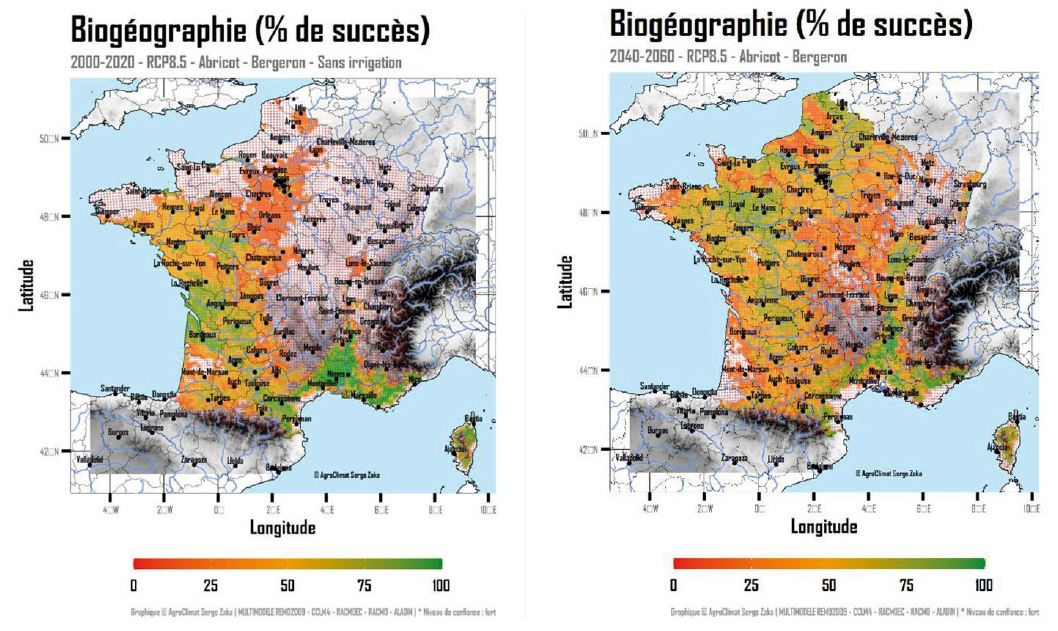

Figure 1 – Comparison of the economic production potential of apricot (Bergeron variety) between 2000–2020 and 2040–2060, without irrigation

Figure 1 – Two maps of metropolitan France compare the economic production potential of the Bergeron apricot variety between the periods 2000–2020 and 2040–2060, without irrigation, under an RCP 8.5 climate scenario corresponding to a high level of global warming. The economic production potential provides a success rate percentage for developing a variety as a main crop. Thus, green areas on the map correspond to a potential above 70%, indicating that the variety is economically viable. Conversely, yellow and red areas indicate that developing the variety as a main crop is not economically viable. The maps indicate that the potential for Bergeron apricot declines in the south and gradually shifts northwards by 2040–2060, particularly to the northern Rhône Valley and in the Pays de la Loire region.

Interpretation: calculating the economic production potential of the Bergeron apricot gives a success rate percentage for developing a variety as a main crop. It is considered economically viable if the potential is above 70% (shown in green on the map). Conversely, yellow and red areas indicate that developing the variety as a main crop is not economically viable. The RCP 8.5 climate scenario used, corresponds to a high level of global warming.

Source: AgroClimat, final report, volume 1, p. 87

Notable developments in the tree-fruit sector

The study shows that the French tree-fruit sector has room for manoeuvre to adapt to climate change, provided that changes in economic production potential across the territory are clearly identified. The progressive creation of new productions and markets, and varietal changes, will need to be planned, and consideration of contrasting regional specificities will be crucial.

Some regions will see their economic production potential erode in the future, especially the Mediterranean basin (Roussillon, southern Languedoc, southern Provence, Corsica) and the southern Rhône Valley, which will suffer from a lack of winter chill and excessive summer heat, as well as significant droughts.

By 2040, a diversification of cultivated species could be envisaged. New species to be introduced could include, among others, citrus, pomegranate, prickly pear, olives, loquats, persimmons, pistachios, mango and avocado. This diversification will be complex to implement because it will require significant technical support and the structuring of new value chains. For olives, for example, equipment (packing, processing) and economic partnerships will need to be developed to meet French demand. By contrast, demand is virtually non-existent for prickly pear and loquats, and very limited for pistachios and pomegranates. The Atlantic coast regions (Brittany, Pays de la Loire, South-West) will mainly suffer from a lack of winter chill rather than from drought. There, diversification based on varietal change is possible by selecting varieties with lower vernalisation requirements (i.e. the period of cold enabling flowering).

Conversely, in the north and north-east of France, climate conditions in 2040 will favour more temperate tree-fruit species than today. The northern Rhône Valley and areas around Besançon, Dijon, Nancy and Metz will benefit from climatic conditions comparable to those currently found in the southern Rhône Valley. They will therefore be able to grow the species currently cultivated there: apples, pears, peaches, apricots and cherries. In the South-West, diversification can be achieved by retaining the same species while introducing varieties with lower vernalisation requirements due to rising winter temperatures. Crops suited to the basins of southern Landes and Lot-et-Garonne could be moved to mid-altitude zones and extend northwards towards Centre-Val de Loire: plums, soft fruit, kiwifruit, strawberries, etc. In these regions, diversification can be based on species and varieties already present in France that have high vernalisation requirements: Golden apple, Franquette walnut and Bergeron apricot. Risks of late frost exist at present, but these species can already extend beyond their current production basins. For species sensitive to winter cold, such as apricot, northward expansion can only take place gradually.

Less difficult adaptations for market gardening

The distribution of vegetable crops should be less affected, regardless of the production system (open-field market gardening, fresh market or processing vegetables), and even more so under glass, where the environment is controlled. Unlike tree-fruit, harvest seasonality can be adjusted. By shifting cropping periods, changing farming practices and adapting varieties, it should be possible to maintain species in production within their current basins. In northern regions, production potential will rise, while it should remain unchanged in the south. Diversification based on new species found in Spain or the Maghreb countries, such as sweet potato, could be possible, but would require the creation of new value chains and sufficient competitiveness to face imports from traditional production areas.

Irrigation, diversification and support for change

The study shows that irrigation improves economic production potential in areas already suited to a crop. With reduced water availability, irrigation will become a very important parameter going forward, and yield gaps between irrigated and non-irrigated farming will widen. Nevertheless, with or without irrigation, production volumes are expected to fall for certain “historic” varieties. Moreover, irrigation will not make it possible to introduce or maintain varieties and species in areas that are not yet, or are no longer, suited to them.

Varieties traditionally grown in southern France will, to some extent, be able to move to more northerly regions or higher altitudes. However, these shifts will not always make it possible to maintain current production levels. Some varieties were selected to suit their historical locations (e.g. Roussillon apricot). The new regions of adoption may have a climate comparable to current basins, but they will not necessarily share the same soil–climate conditions, which would translate into a moderate loss of production potential.

To maintain French production, species and varieties will therefore have to be diversified, both at production-basin level and on individual farms. This diversification will need to be gradual, as the climate is continually evolving. In an ageing orchard, for example, it will be necessary to replant a new variety and/or species while keeping the previous one in place, to avoid a risky transition with overly variable yields. Over the next two decades, late frost (mainly in the North–North-East) and vernalisation requirements (South) will vary considerably from one year to another. Maintaining species or varieties with different sensitivities to these parameters on the same farm will help avoid unproductive years. This diversification is all the more necessary because, for economic and social reasons, farms have tended to specialise in recent years.

To support these adaptation and diversification efforts, the study’s authors consider that maintaining dynamic research and experimentation programmes is a priority. They should focus on varietal improvement (to make plants better adapted to future climatic conditions) and, more generally, seek to support the evolution of production basins. Work should focus on cross-cutting adaptation traits, such as root-system development, so that plants are more resilient to irregular water supply.

Moreover, the geography of production is not the only variable to consider. Other economic or social parameters must also be taken into account to support basin-relocation strategies: location of tools and infrastructure linked to the value chain (packing platforms, logistics, processing tools, etc.), risk-sharing, changes in food consumption, etc. Incorporating and anticipating these issues in public policy will depend on the political and socio-economic context in the years ahead.

2. Four foresight scenarios for the fruit and vegetable sectors by 2040

The scenarios below, which are deliberately contrasting, explore different probable futures for the fruit and vegetable sectors by 2040. They do not claim to predict reality in advance but are an invitation to projection and reflection. They are based on literature reviews, interviews and workshops with sector stakeholders. These scenarios take account of biogeographical maps and other sets of social, political, economic and technological variables, etc. (Figure 2).

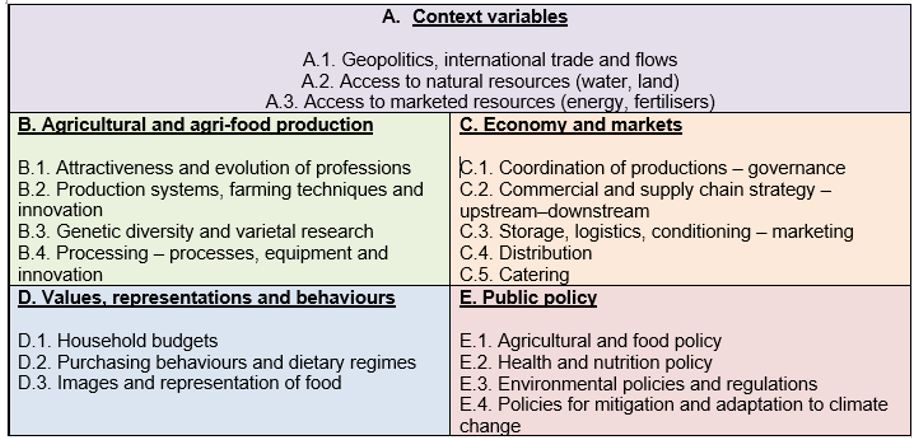

Figure 2 – System of variables used to analyse the present situation and develop future scenarios

Figure 2 – A table presents the system of variables used to analyse past and present trends in the fruit and vegetable sectors and to construct development scenarios. The main variables influencing these sectors concern the context in which they operate (e.g. geopolitics, natural resources), agricultural and agri-food production, the economy and markets (e.g. marketing strategies, market access), the values, representations and behaviours of households and farmers, as well as public action. These factors vary in contrasting ways across each of the scenarios developed.

Source: CERESCO, final report, volume 2, p. 12

European food sovereignty

This first scenario describes a European Union (EU) facing growing difficulties in sourcing (food, agricultural inputs) on international markets. In response, it adopts a productivist policy to support continent-wide food sovereignty and secure its food value chains. Protectionist measures (higher customs duties, mirror clauses, etc.) are implemented to favour European production. Downstream actors invest upstream to secure their value chains and control their costs.

In this scenario, a short-term logic prevails. There is no specific public support to accompany the evolution of the sectors in the face of new biogeographical constraints. All links in the food sector, from production to distribution, prioritise adopting earlier or more resilient varieties rather than working on shifting production basins and developing new productions and markets (citrus, olive, sweet potato, etc.), which, in their view, involve overly uncertain investments.

The hyperspecialisation of agriculture around a small number of productions that better withstand climate constraints can be observed, as well as the deployment of technological solutions addressing weather-related problems (optimised water use, anti-hail and anti-insect nets, etc.). Irrigation use is widespread and local conflicts over water increase. Winter production diversifies, while summer production becomes increasingly difficult (e.g. droughts). Fruit and vegetable supplies depend on imports from European neighbours, particularly during the hottest summers.

Environmental awareness

This second scenario describes Europe experiencing health and environmental crises, with several scandals, including diseases linked to pesticide exposure. Under pressure from civil society, supported by the scientific community and NGOs, the EU launches an ambitious plan to protect its strategic natural resources, water, soils and biodiversity in particular. It places agroecology at the heart of this strategy and deploys an incentive-based policy fostering agricultural entrepreneurship. Import standards protect the European market from international competition that imposes less stringent production rules on its agriculture.

In this context, increased funding via operational programmes (the EU Common Organisation of the Markets in the fruit and vegetables sector) is channelled to encourage the reorganisation of production basins in line with evolving biogeographies. The priority is the progressive renewal of French orchards to adapt to winter cold (mainly in the North and North-East), enable vernalisation (in the South) and better manage high temperatures. For new productions (sweet potatoes, loquats, prickly pears, peanuts, pistachios, etc.), major communication and outreach efforts are made alongside productive investments. These support campaigns take account of nutrition policies and create outlets for new French fruit and vegetables (loquats, prickly pears, pomegranates, etc.).

At the same time, reducing inputs and transitioning to new varieties and species require significant technical learning and adaptation of production tools. The risk of tensions over supply, in quantity (lower yields) and quality (sizes, blemishes, etc.), is high. Imports are limited and alternative solutions become widespread: broader size ranges, development of “fourth-range” products (ready-to-use fresh produce), etc.

“Wheat, wheat, wheat!”

This third scenario anticipates increased globalisation in which European states, including France, are weakened by repeated crises (economic, migratory, climatic, health, etc.). They then prioritise the competitiveness of economic actors by simplifying and/or lifting regulatory constraints, particularly environmental ones. Corporate agriculture8 increasingly becomes the norm and prioritises arable crops. The number of fruit and vegetable farms falls drastically.

In this context, there is no national-level strategic thinking on the evolution of production basins. Producers without the technical or financial means to invest, or those close to retirement who no longer wish to, abandon the species most at risk after a few years of poor yields. Tree-fruit value-chains suffer the most from this disengagement. Private R&D efforts and farms concentrate on fast-turnover, high-yield crops (soft fruit such as strawberries, certain vegetables), which allow better adaptation to demand fluctuations. Some productions collapse (apricots, apples, pears, cherries, etc.), notably in Occitanie, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur and Corsica. Competition between actors prevents the investments needed to develop new productions and markets adapted for the long term. The fruit and vegetable sector becomes hyperspecialised in a few species that are particularly resilient, profitable or suited to greenhouse cultivation, which expands.

Opportunistic reconquest

In this fourth and final scenario, France launches an ambitious conquest plan for fruit and vegetables to meet social and economic objectives, notably strengthening food security and the nutritional quality of diets. The country sees climate change as an opportunity to win back market share from Spain and Italy, which face severe climate constraints. France seeks to become Europe’s leading supplier of natural vitamins by mobilising all links in the fruit and vegetable value chain and increasing national production.

Funding from ambitious budgetary choices supports the development of new productions and value chains. It is targeted in line with evolving production areas. Fruit and vegetables traditionally produced in Spain and southern Italy (tomatoes, courgettes, citrus) are prioritised, given the difficulties faced by those two countries. France has an opportunity to position itself as an exporter to these markets at European level. The regions most suitable for such production, such as Brittany, Normandy and Nord-Pas-de-Calais, receive particular support: training, investment in suitable equipment, marketing, creation of quality labels, variety–terroir trials to identify the most interesting varieties for each area, etc.

Conclusion

This note focuses on the consequences of changes in the geography of fruit and vegetable production in France in the context of climate change. It shows that shifting production basins will be necessary to maintain national fruit and vegetable production levels. Diversifying the species and varieties grown, will also need to be prioritised.

These changes will require supporting farms to maintain the sector’s competitiveness and to make investments. This support must be both technical (e.g. cropping systems, varietal innovation) and economic (e.g. contractual and insurance systems). Achieving a better match between production and consumption will be another challenge in the coming years, while taking account of the fundamentals of agricultural economics and public-health recommendations. The development of certain products (e.g. nuts, sweet potatoes) will, in particular, need to be supported.

The findings and scenarios presented in this study contribute to reflections on the future of the fruit and vegetable sector in France. This work has made it possible to explore likely developments in the fruit and vegetable sectors. It is now up to all stakeholders to take up these elements to make decisions that will bring about the most desirable future.

Alice de Bazelaire, Pauline Delpech, Bertrand Oudin (CERESCO)

Serge Zaka (AgroClimat)

Julie Blanchot, Marie Martinez (Centre for studies and strategic foresight)

Notes de bas de page

1 Ceresco, AgroClimat, 2025, Quels futurs pour les filières fruits et légumes françaises d’ici 2040 ?, report for the Ministry of Agriculture, Agrifood and Food Sovereignty: https://agriculture.gouv.fr/quels-futurs-pour-les-filieres-fruits-et-legumes-francaises-dici-2040

2 MASA, Plan de souveraineté pour la filière fruits et légumes, 2023.

3 CGAAER, Prospective pour l’industrie agroalimentaire française à l’horizon 2040, 2025

4 FranceAgriMer, Étude sur les tendances de marché pour la pomme de terre française, 2024

5 The Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) presented in the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report correspond to four trajectories for the evolution of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere for the 21st century and beyond.

6These are: winter frost, end date of vernalisation (period of cold enabling flowering), flowering date, maturity date, drought intensity, post-flowering frost, post-flowering fruit drop (excess water at flowering) and heatwave risk.

7 GAEZ methodology, which makes it possible to assess land resources and agricultural potential.

8 Purseigle, F., Nguyen, G. and Blanc, P. (dir.), 2017, Le nouveau capitalisme agricole. De la ferme à la firme, Presses de Sciences Po.