Proposed Free Trade Agreement between the European Union and India: Opportunities and Risks

Partager la page

Les notes d’Analyse présentent en quatre pages l’essentiel des réflexions sur un sujet d’actualité relevant des champs d’intervention du ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Souveraineté alimentaire. Selon les numéros, elles privilégient une approche prospective, stratégique ou évaluative.

Analysis n°219

Negotiations aimed at establishing a free trade agreement1 (FTA) between the European Union (EU) and India, initiated in 2007 and subsequently suspended in 2013, resumed in June 2022. To contribute to the formulation of France’s position, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty commissioned a study2 to anticipate the risks and opportunities associated with this project for selected sectors. The work was carried out by Abcis and the Association for Technical Research in Sugar Beet (ARTB). This note summarises the main findings, focusing specifically on the beef and sugar sectors. For both commodities, Indian productions seem competitive. For instance, the government regularly subsidises sugar exports to regulate the domestic market. Additionally, the beef sector is increasingly structured for export, although it has not yet gained access to the European market, primarily due to sanitary regulations.

Introduction

Global trade has grown substantially since the signing of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947. By 2023, the value of international trade was 370 times higher than in 1950. This growth has been supported by multilateral initiatives, most notably the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. In recent years, however, the WTO has faced significant challenges. Global events with worldwide repercussions (such as conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East) have affected multilateral relations. Some states have sought to disengage from the institution, leading to internal difficulties, including unrest within the Dispute Settlement Body3. The coordination of global trade, previously almost entirely entrusted to the WTO, is now increasingly questioned. In this context, countries sometimes pursue bilateral negotiations, which may result in FTAs covering all or part of their trade.

This is the case for India and the EU, which initiated negotiations in 2007, suspended them in 2013, and announced their resumption in May 2021. A political conclusion was initially envisaged for early 2024, but negotiations are still ongoing. The introduction of tariff concessions between the two partners could have significant and varied implications for agricultural sectors.

In preparation for defining European and Indian offers, the French Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty sought to assess the strengths and weaknesses of several agricultural sectors to better understand the negotiation stakes. Consequently, in 2023, a study was commissioned to Abcis and ARTB. Its primary objective was to characterise differences between selected Indian and French sectors, particularly in terms of price and non-price competitiveness. The study also aimed to provide a more detailed description of existing tariff and non-tariff barriers between India and the EU. Finally, it sought to identify the risks and opportunities associated with exports of certain key products to India, and to estimate the potential effects of trade liberalisation.

India: Producing to Feed the World’s Largest Population

A Vast Consumer Base

India is both an agricultural giant and an enormous consumer market. The country covers 3.3 million km², including 180 million hectares of agricultural land. Since 2023, it has been the most populous nation in the world, with 1.4 billion inhabitants, and ranks as the fifth-largest economy, despite a relatively low per capita gross domestic product (GDP). With highly variable income levels and a significant proportion of the population living in poverty4, food security is a strategic concern and has been a central objective of India’s agricultural and trade policy since independence in 1947.

Food security has historically been pursued through several mechanisms: promoting national self-sufficiency in production, improving economic access to food for specific social groups or regions, implementing storage policies to protect the domestic market against shocks, and administering prices and export restrictions.

Indian agriculture has experienced strong growth in recent years. The government has supported key sectors to increase production and supply the domestic market. The development level of several industries now allows for, or at least contemplates, export opportunities. Nevertheless, India is not yet a major global player in agri-food trade. Some products, however, are heavily dependent on exports for economic viability, and international sales also serve to stabilise domestic markets and prices.

Beef: Gradual Entry into the International Market

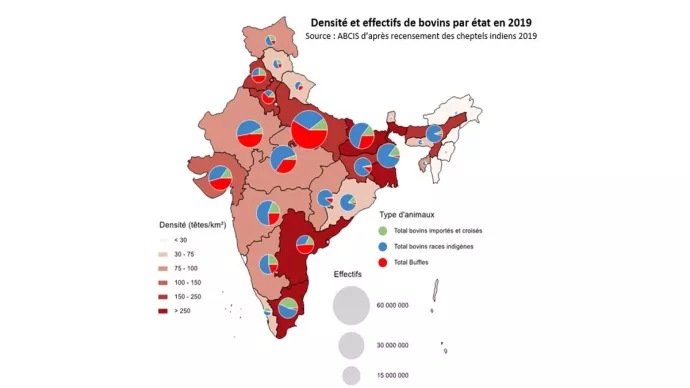

In 2022, India held the world’s largest bovine herd and ranked fifth in beef production and fourth in exports. Consumption of beef is prohibited in most Indian states for religious reasons. Nevertheless, more than two-thirds of national production is consumed domestically, primarily by Muslims and Christians, who together constitute just under 20% of the population. Indian law permits only the export of deboned, frozen buffalo meat, known as carabeef (from the Filipino term carabao, or water buffalo).

Since the late 2000s, part of the beef industry has become increasingly structured, resulting in the coexistence of two distinct supply chains. The first serves the domestic market and remains heterogeneous and fragmented. The second, oriented towards exports, is dynamic and well-organised. This export-oriented sector has contributed to national production growth and helped establish India’s position in the global market. In 1992, less than 4% of Indian beef production was exported, rising to 15% in 2001 and nearly 32% in 2022 . The international market has thus become a structural outlet for these products.

The three largest Indian exporters account for nearly two-thirds of the value of exported beef. Allana Group is the dominant player, representing 40% of exports, followed by HMA Agro Industries Ltd (15%) and Hind Group (10%). These companies operate modern abattoirs and maintain fleets of refrigerated trucks.

Sugar: The International Market as a Tool for Domestic Regulation

The Indian sugar sector has been developed primarily to meet domestic demand and to maintain rural employment, following a family-farm model in which growers own the land and carry out fieldwork. This model involves 25 to 50 million cane growers, who are often poorly organised. The number of sugar mills is also very high, but many are outdated. With rising GDP and population growth (+12% between 2011 and 2021), sugar consumption has increased by an average of 500,000 tonnes per year.

Balancing supply and demand remains a major challenge for the country, complicated by rising consumption, fragmented production capacity, ageing infrastructure, and variable cane yields due to weather conditions, particularly the monsoon. Consequently, India’s sugar trade policy—both imports and exports—has long served as an adjustment variable through import tariffs and export subsidies, which have been the subject of disputes at the WTO6. Since the late 2010s, a new ethanol policy has allowed a significant portion of surplus cane production to be absorbed.

Historically dependent on domestic production levels, Indian sugar exports have increased substantially in recent years, averaging over 5 million tonnes per year between the 2019 and 2022 campaigns, representing nearly 20% of total production. However, the country’s export capacity is contingent on government financial support, which may be limited in the future by potential WTO rulings. Moreover, strong domestic consumption growth means that adverse weather events or a significant reduction in cultivated areas could constrain export volumes. The emerging ethanol market could also stabilise or even reduce the cane production surplus. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)7, Indian ethanol production is expected to rise from 45.7 million hectolitres (Mhl) in 2021 to 110 Mhl by 2031. In any case, exports will remain a flexible outlet for surplus production.

Variable Competitiveness

For Indian commodities, the exchange rate between the rupee and major currencies of developed economies is a key factor in competitiveness. Between January 2012 and May 2023, the Indian rupee depreciated by 38% against the US dollar and by 26% against the euro, enhancing the competitiveness of Indian exports.

Most beef produced in India derives from the dairy sector. No consolidated data are available on farmers’ purchase prices, preventing direct comparison of production costs between India and the EU. Comparing Indian export prices on a free-on-board (FOB) basis8 with those of major exporters (Argentina, Brazil, Australia, United States, etc.) demonstrates the high international competitiveness of Indian beef. In 2022, deboned frozen cuts exported from India averaged €2.24/kg carcass weight equivalent, one to over two times cheaper than competing products. Some investments made since the early 2000s, such as modernising export-oriented abattoirs and investing in refrigerated truck fleets and electricity generators, have slightly reduced international competitiveness.

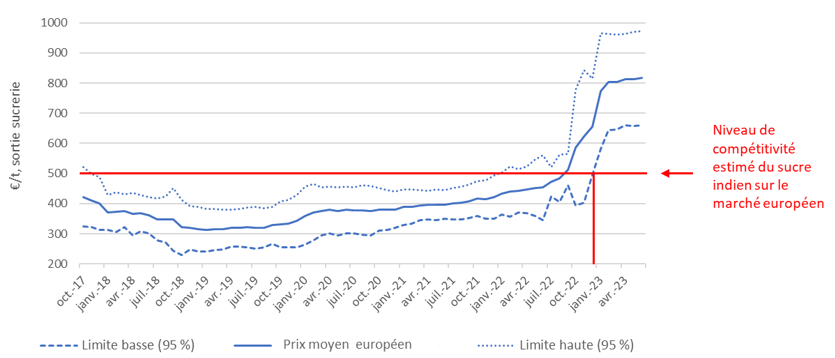

The competitiveness of the Indian sugar sector, analysed for white sugar ready for consumption (representing 60% of exports), is lower than that of the beef sector. Considering freight and insurance costs from India to the EU of around USD 100/t of sugar (€90/t), Indian sugar is competitive whenever European sugar trades above €500/t (figure 1)9. Furthermore, because the primary objective for India is domestic food security, international prices have limited influence on production and exports. When a production surplus risks depressing domestic prices, the government provides export subsidies to sugar producers. For example, during the 2019–2020 campaign, a subsidy of 10,448 INR per tonne (€141/t) was granted, enabling the export of 5.8 Mt of sugar out of the 6 Mt target.

Figure 1 - Evolution of the Average Sugar Price (euros per tonne) in the EU Since the End of Quotas and Indian Competitiveness

This graph shows the evolution of the average price of sugar in the European Union from October 2017 to April 2023. The bar symbolizes the price reaching over €500/t in early 2023, which corresponds to the estimated competitiveness level of Indian sugar on the European market.

Note: The blue line shows average price. The 95% interval rate (dotted blue) corresponds to the mean adjusted by ±2 standard deviations. Data from the United Kingdom are included in the calculation of the average price until the end of 2020. The red line show the estimated competitiveness threshold.

Source: ARTB & European commission

Limited Access to the European Market, Varying by Sector

European markets for beef and sugar remain protected by high tariffs and non-tariff measures. Indian beef currently cannot enter the EU due to lack of approval, while sugar benefits from duty-free quotas.

Beef: No Access to the European Market at Present

In general, exports of fresh beef (unprocessed) and certain processed beef products to the EU are subject to an ad valorem duty of 12.8%, supplemented by a specific duty ranging from €114 to €304 per 100 kg net. The average applied rate therefore varies between 30% and 40% of the product value, depending on market conditions and the type of beef. Tariffs are lower for certain processed beef products, such as corned beef (16.6%). Preferential access to the EU market does exist in some cases10, such as annual consolidated quotas granted to certain exporters under the 1994 WTO Agreement on Agriculture (the so-called “Hilton” quotas11) with reduced tariffs of 20%. Other preferential quotas include those arising from the WTO “hormone panel” ruling12 (duty-free) and various duty-free or reduced-tariff quotas established under bilateral agreements, such as with Canada13.

However, India currently lacks the necessary sanitary approval and suffers from deficiencies across the entire beef supply chain (e.g., near-absent traceability), preventing any exports to the EU. As India does not enjoy preferential access, no trade flows currently exist.

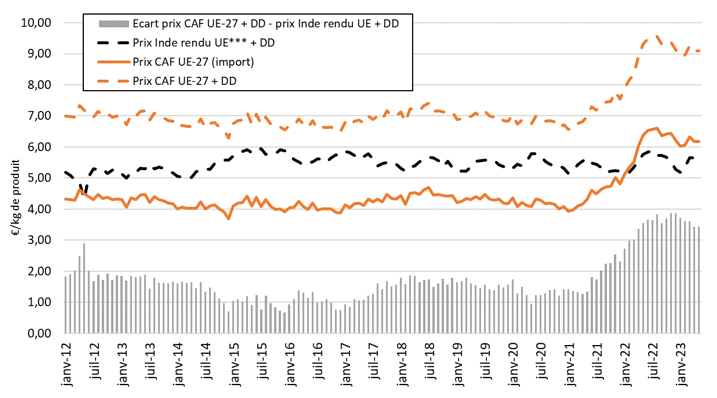

Within the scope of the study, the competitiveness of potential Indian imports was assessed by constructing an export price (including transport) for Indian frozen deboned beef delivered to the EU. The results indicate that, over the period from January 2012 to May 2023, Indian frozen deboned beef would have been more competitive than the average prices of beef imported by the EU. The average price difference was €1.73/kg, ranging from €1/kg to €3.50/kg.

This result, however, has two limitations: the customs classifications used group a wide variety of products of different qualities, and actual access to the European market would require investments that would reduce the competitiveness of Indian beef.

Figure 2 - Comparison of CIF (Cost, Insurance, and Freight) prices for frozen deboned beef imports by the EU-27 and estimated Indian export prices delivered to the EU-27

This graph compares the CIF (cost, insurance, and freight) prices of frozen boneless beef imports into the EU-27 with the prices of Indian exports to the EU as estimated by the authors of the study. We can see that the curves intersect from 2022 onwards.

Source : Abcis, final report p 287, from Banque de France, OECD, Eurostat, Indian customs data

Note 1: CIF (Cost, Insurance, and Freight) prices indicate that the import price of a commodity includes not only the product price itself (the cost to the buyer) but also the insurance cost and the cost of transporting the goods to the purchaser.

Note 2: the solid orange line shows the estimated CIF price of Indian beef delivered to the EU, and the dotted orange line includes customs tariffs. The dotted black line shows the actual price of beef imported to the EU. Grey bars show the difference between the two prices.

Sugar: Limited but Fully Utilised Quotas

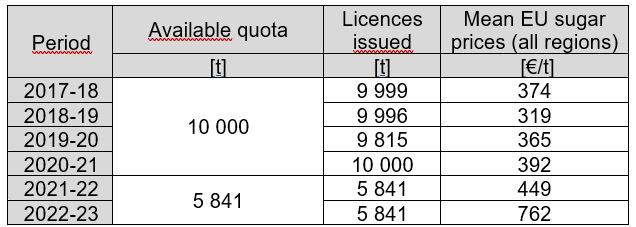

Full customs duties for sugar intended for refining reach €339/t, and €419/t for white and speciality sugars (e.g., cane), excluding preferential access to the European market. Indian sugar benefits from preferential access to the EU market through a duty-free CXL quota14. The volume of this quota was set at 10,000 tonnes per campaign until the 2021–2022 campaign. Since then, it has been reduced to 5,841 tonnes following the division of quotas between the EU and the United Kingdom due to Brexit (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Indian CXL sugar quota granted by the EU since 2017–2018, actual licences issued, and the average level of EU sugar prices

This table shows the volumes of CXL quotas for Indian sugar granted by the European Union from 2017 to 2023, as well as European sugar prices for the same years. We can see that the quotas are systematically filled, regardless of the price level and the year.

From 2017 to 2023, the quota granted to India was almost fully utilised in each campaign. Consequently, regardless of the sugar price level in the EU—including periods of low prices, such as the 2018–2019 campaign (€319/t)—India was able to export sugar. The global market thus served as a release outlet: Indian sugar could be sold at a loss to mitigate imbalances between supply and demand in the domestic market and to reduce downward pressure on domestic prices.

Risks but Few Opportunities for European Stakeholders

Indian Production Expected to Continue Growin

According to the FAO and OECD, Indian production is projected to continue increasing through 2031. For beef, production is expected to rise by 185,000 tonnes (+7%) compared with 2021, resulting in higher domestic consumption (+87,000 tonnes, +8%) and exports (+97,000 tonnes, +7%).

Between 2021 and 2031, Indian sugarcane production is expected to increase by 21 Mt (+5%), while annual sugar production would grow by 400,000 t (+1%). Simultaneously, domestic sugar consumption in India is projected to rise by 3 Mt (+12%). Over the same period, ethanol production is expected to expand by +240%, reaching 110 Mhl by 2031, with the proportion derived from sugarcane increasing from 13% in 2021 to 28% in 2031. Ethanol consumption is expected to grow by 220% to 115 Mhl. Based on these projections, India’s foreign trade in ethanol is likely to remain stable, while sugar imports are expected to increase by 341,000 t (+126% compared with 2021) and exports to decline by 56% to 2.8 Mt.

These projections, representing average expected trends, assume a given macroeconomic environment with policy and market stability, while markets are generally volatile.

A Risky Agreement for European Production

The large production capacity—whether structural or cyclical—and the competitiveness of Indian beef and sugar sectors, combined with government export subsidies, pose risks to European sectors, particularly if a free trade agreement (FTA) were signed, improving market access for Indian products in the EU.

Indian beef production is competitive for export but currently does not meet the quality standards required for the European market. Upgrading the sector is feasible but would require investments in traceability, sanitary management, and other improvements. Access to a major market such as the EU, which is significant for the image of Indian beef, could accelerate existing initiatives to improve production standards. However, these improvements would entail additional costs, limiting the relative competitiveness of Indian beef compared with other EU imports.

The competitiveness of the Indian sugar sector relative to European production is more limited. Nevertheless, given that the current EU quota is systematically fully utilised, granting an additional quota under an FTA would represent a risk for sugar beet and sugar-producing regions in Europe. Sugar mills must maintain a minimum production threshold to remain profitable, so additional Indian imports could threaten entire production areas. Moreover, the potential inclusion of speciality sugars (e.g., cane sugar) in such a quota could undermine production in French overseas regions, the primary supplier in this European niche market.

Opportunities for Certain By-Products and Other Sectors

While there is no offensive interest for the EU regarding sugar or beef, some by-products from these sectors could benefit from preferential or expanded access to the Indian market. This includes bovine hides and other raw or processed animal products, which are currently subject to tariffs and non-tariff measures that restrict or prohibit trade.

However, the main offensive interests of European agriculture lie in other sectors, notably certain plant-based products such as vegetable seeds, barley, and malt. More generally, as with most recent bilateral agreements negotiated by the European Commission, the EU’s offensive interests are concentrated outside agriculture: electronics, chemicals (rubber and plastics), machinery production, and other industrial sectors14.

Conclusion

Indian sugar and beef production is undeniably competitive for export, and the Indian government regularly intervenes to encourage exports, particularly to stabilise the domestic market, irrespective of international market conditions. The export potential of India is therefore well established for the sugar and beef sectors.

The potential of other sectors remains to be determined. For example, government ambitions to expand dairy production will face increasing climate-related challenges, which are already significant in the country. The strategic issue of water access, both in terms of quantity and quality, already central, is likely to become critical in the coming years. Currently, Indian regulations, established by the federal government or individual states, are far less stringent than EU standards and are likely to remain so in the near future. For instance, there is no mandatory traceability system in Indian livestock farms. This regulatory environment, unfavourable to exports to the EU, could gradually evolve, particularly under the influence of companies aiming to develop in India and export their products.

In this context, although certain opportunities exist in the Indian market for a limited number of European agricultural products, it appears prudent to maintain protective measures at the EU level to limit access of certain products to the European market. Their liberalisation could destabilise the market, especially since several concessions have already been proposed or implemented under other free trade agreements, notably with New Zealand and Mercosur.

Baptiste Buczinski - Institut de l’élevage

Alexis Patry -ARTB

Amandine Hourt - Centre for studies and strategic foresight15

Notes de bas de page

1 - Treaty signed between two or more countries to facilitate trade and eliminate barriers to commerce.

2 - Buczinski B., Patry A., Bouzidi M., Cassagnou M., Désolé M., 2024, Opportunités et risques commerciaux dans le cadre des négociations d’un accord de libre-échange entre l’Union européenne et l’Inde. Exemples des filières laitière, viande de volaille, bœuf et sucre, 307 pages.

3 - Banque de France, 2021, « Le blocage de l’OMC, un révélateur de la crise du multilatéralisme ? », Bulletin de la Banque de France.

4 - According to the 2022 World Inequality Report, the income of the richest 10% of Indians was 22 times higher than that of the poorest 50%.

5 - Buczinski B., Patry A., Bouzidi M., Cassagnou M., Désolé M., 2024, op.cit., p 47.

6 - OMC, 2021, Inde : mesures concernant le sucre et la canne à sucre, Rapports des groupes spéciaux.

7 - OCDE, FAO, 2022, Agricultural Outlook 2022-2031.

8 - Free on Board (FOB). This price does not include transport costs, export duties, or any insurance related to shipment and export.

9 - Regardless of the competitiveness of Indian sugar, exports to the EU remain possible as long as a preferential tariff advantage exists (see Section 2.2).

10 - Preferential market access can take the form of duty-free and quota-free access, preferential tariffs or duties (with or without quotas), and preferential rules.

11 - “Hilton” quota: an import quota with preferential duty for high-quality cuts from young grass-fed male cattle.

12 - “Hormone panel” quota: an import quota for beef established by the EU in 2009 as compensation for its 1998 ban on products from hormone-treated animals.

13 - Décision (UE) 2017/37 du conseil du 28 octobre 2016.

14 - Trade Impact B.V., 2023, Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment of the EU-India trade and investment agreements.

15 - At the moment when this note was written.

Voir aussi

Plan de souveraineté pour la filière fruits et légumes

29 avril 2024Production & filières

Relocalisation en France de certaines productions de fruits et légumes

21 mars 2025Conseil général de l’alimentation, de l’agriculture et des espaces ruraux

Plan de souveraineté de la filière fruits et légumes : 8 millions d’euros dédiés à la rénovation des vergers arboricoles pour 2025-2027

18 juillet 2025Filières végétales