French Organic Farming in 2040: a foresight exercise

Partager la page

Les notes d’Analyse présentent en quatre pages l’essentiel des réflexions sur un sujet d’actualité relevant des champs d’intervention du ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Souveraineté alimentaire. Selon les numéros, elles privilégient une approche prospective, stratégique ou évaluative.

Analysis n°221

French Organic Farming in 2040: a foresight exercise

In 2023, organic farming (OF) accounted for 14% of farms in France, 19% of agricultural jobs, 10.4% of agricultural area, and 6% of food sales. After two decades of growth, the organic sector has been experiencing a severe crisis since 2022, making it difficult to achieve the targets previously set by successive governments. In this context, a foresight study1 was commissioned by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty. Conducted by Ceresco and Crédoc, the study aimed to explore probable development trajectories for OF up to 2040. This note presents the four scenarios emerging from the study. It highlights the potential marginalisation of OF compared with other approaches also emphasising environmental promises. It also underlines the importance, for organic food consumption, of prices, the perception of labels, and the expected benefits (health, environment, etc.).

Introduction

The market for organic farming (OF) products grew almost continuously until 2020, with particularly strong growth from 2012 onwards. Products such as milk, eggs, fruits and vegetables became emblematic of the organic offer. However, after the unusual year of 2020 (Covid and lockdowns), when sales increased by 10.2% in value, the organic market contracted by 0.5% in 2021 and 4.6% in 2022, reaching €12.1 billion in France in 2023. More recently, it has stagnated in value and declined in volume (-7% between 2022 and 2023). Organic products have also been affected for several years, and especially since the war in Ukraine, by inflation (+7.7% in 2023, +4% in 2022), even if lower than overall food inflation2.

The number of organic farms has followed similar trends. It rose sharply from 13,000 in 2008 to more than 60,000 in 2023, but this increase has slowed significantly since 2021. Areas under conversion have been declining every year since 2021 (e.g. -30% in 2023), while certified areas increased by only 3.2% in 2023, compared with double-digit growth in previous years.

These shifts have led OF stakeholders to question the future of their sector and, in a context of renewed ambition (the “Ambition Bio 2027” government programme), a foresight study was launched in 2023 by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty. Entitled “What Futures for the French Organic Sector to 2040?”, the study set out to provide a retrospective and current overview of the French organic sector (including farming and processing chains, distribution and consumption, research, training and education activities), then to explore various probable future trajectories. This work, entrusted to the consultancies Ceresco and Crédoc, was published in August 2025.

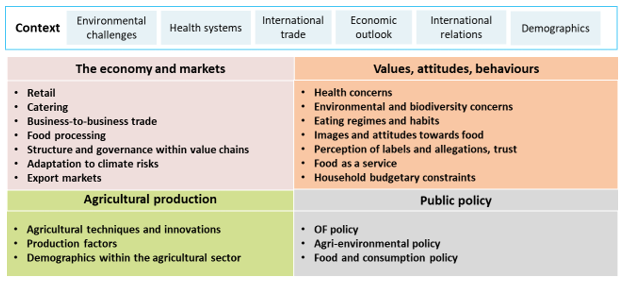

The first phase of the study enabled a diagnosis of the OF sector and identified the main key variables driving its evolution (Figure 1). A comparison with four other countries (Spain, Germany, Denmark, United States) completed this overview. The second, prospective phase consisted of formulating future hypotheses and constructing scenarios, drafted from the reflections of a foresight group bringing together sector stakeholders. Recommendations for action, made by the consultancies, were proposed in the third phase.

Figure 1 - System of variables used to analyse the present situation and build future scenarios

This figure lists the variables that were used to construct the prospective scenarios. They are grouped into five thematic components.

Source : Ceresco

Reading note: These 20 variables were selected as they were considered the main factors influencing the future of the organic sector. They were grouped into five components. Each variable was discussed within the foresight group and future hypotheses were drawn up for each. Crossing these hypotheses then made it possible to develop and draft four scenarios.

Scénario 1: In Search of Growth and then Resilience, the Organic Sector Non-Priority

From 2024 to 2030, economic growth remains the primary political objective. Globalisation, international trade and market competition continue, contributing to the reduction of food prices. These dynamics accelerate the depletion of natural resources (e.g. fossil fuels, minerals, water) and increase the frequency and severity of climatic and economic shocks. Environmental concerns are secondary in public policy and for the majority of consumers, who do not take into account the environmental impacts of production methods when making their purchases.

In this context, organic products disappear from supermarket shelves, and the specialised economic fabric disintegrates (e.g. many processors specialising in organics go bankrupt). This prevents the recovery of the sector, once hoped for, after the 2021–2023 crisis. Short supply chains for organics persist in rural areas, where production and consumption are geographically close, and in affluent urban and peri-urban areas. OF, now marginalised, targets a loyal and/or affluent clientele seeking products perceived as healthy and natural. Links between producers and consumers are strengthened through digital tools (e.g. online purchasing platforms).

From 2030 onwards, crises of access to strategic resources (copper, phosphates, etc.) and climate-related shocks multiply, destabilising markets and disrupting supply chains. Certain food products reach very high, even prohibitive, prices, and shortages are sometimes observed. Citizens’ purchasing power diminishes, food insecurity rises, and social movements denounce growing inequalities. Gradually, borders close, trade flows contract, and new populist governments take power, both in Europe and elsewhere.

Food systems must then adapt to the reduced and uncertain availability of agricultural inputs (fertilisers, plant protection products, etc.). Conventional supply chains are destabilised, as they are based on an intensive agriculture model guaranteeing large and stable volumes. Downstream actors and distribution networks backtrack on agricultural integration, which had developed in the latter half of the 2030s. They mobilise their financial resources to safeguard the core of their economic activity.

In this context of enforced frugality, OF practices, less dependent on inputs, expand over a few years, albeit without formal certification. Some producers, due to irregular access to inputs, practise intermittent OF and do not necessarily valorise this production mode. New forms of peer-to-peer agronomic advice emerge. Organic farmers who have continued their activity throughout the crisis period become key technical reference points and gain particular influence. Part of their income derives from training activities. Their techno-economic results are more stable over time due to their experience. However, they encounter difficulties in differentiating themselves from other producers, increasingly numerous, claiming to produce without synthetic inputs.

By 2040, the European organic label, support policies and national governance structures for the sector no longer exist. New organic standards emerge at the initiative of local authorities. Without national harmonisation, some are more flexible than the current versions. Communication, practices and potential support measures vary between territories.

Scenario 2: The Triumphant “Third Way” and a Marginalised Organic Sector

In the second scenario constructed by Ceresco and Crédoc, the multiplication of crises linked to climate change triggers a growing awareness of environmental challenges among the population and businesses, and it becomes more strongly embedded in public policy. International agreements are concluded with the aim of reducing the environmental footprint of all sectors of the economy, including agriculture. Transnational private actors in the agricultural and agri-food sectors adopt these new rules of the game. They seek to distinguish themselves by highlighting their sustainability initiatives, in response to the concerns of consumers and their shareholders (e.g. CSR commitments). They support the deployment of technically more environmentally ambitious farming systems (e.g. soil health), but which remain less stringent than those required under OF. All of these initiatives progressively structure, on a large scale, a “third way”, i.e., an alternative to both OF and conventional agriculture, with environmental claims. This enables these actors to claim environmental added value, while limiting the additional costs of agricultural production.

Thanks to effective communication and marketing, the market share of “third way” products increases rapidly. Within a few years, it becomes the reference approach in terms of environmental benefits. In parallel, OF gradually loses its capacity to influence consumers and public authorities. Less well-structured and lacking unity, sector stakeholders fail to demonstrate the environmental added value of their products. Public support for OF is reduced and partially redirected towards the “third way”.

The crisis that hit OF in the early 2020s continues. Organic products lose market share. The visibility and reputation of the organic label decline in mass retail, despite sector-led communication campaigns, which prove largely ineffective. Consumer attention to the organic label continues to diminish, as it is challenged by the “third way”. A decrease in consumption, albeit less severe, is also observed in specialised organic retail. By 2040, organic products account for less than 3% of household food expenditure (compared with 5.6% in 2023), and only a small proportion of consumers continue to purchase them. These include notably young graduates, well-informed and often socially engaged, who are reluctant to consume “third way” products, as well as older individuals who have long been convinced.

These developments have major impacts upstream in the organic sector. The number of producers falls sharply, with many reverting to conventional farming. Only a small minority of organic farmers remain, sustained by a core group of consumers. The processing link is also weakened, and companies working exclusively with organic products disappear. However, within this generally negative context, a few organic supply chains restructure or even expand, mainly around competitive export-oriented production (e.g. apples), and in certain European markets where the “third way” has failed to establish itself.

Scenario 3: a “Light” Organic Standard for a Competitive and Mainstream Sector

Extreme climatic events (droughts, floods, etc.), particularly affecting major powers such as the United States or China, contribute to a growing general awareness of environmental challenges. An unprecedented mobilisation of civil society (activists, scientists, etc.) emerges, widely relayed by the media and social networks. After several failures (e.g. COP 29 and subsequent ones), an ambitious international agreement is reached in 2032 to tackle major global challenges, notably the preservation of resources, climate, biodiversity, and soil protection, while also harnessing the economic opportunities associated with the ecological transition. Treaties are concluded to establish trade standards that allow customs duties to be adjusted according to the environmental impacts of products, following the model of the carbon border adjustment mechanism.

At the European level, stakeholders in French organic supply chains unite to have OF recognised as the benchmark for agricultural production. These efforts are supported by the growing body of scientific evidence confirming the positive externalities of organic systems for human health and the environment (e.g. biodiversity, soil health). A new Green Deal sets ambitious environmental objectives, such as the phasing out of plant protection products by 2040. To achieve this, the multiplication of conversions is considered a priority and the transition towards OF accelerates significantly.

Environmental ambitions are reinforced, for example through the introduction of input taxes. These measures partially internalise the negative externalities of certain agricultural practices, thereby increasing production costs. To limit food inflation, public authorities encourage economic actors to rationalise processes throughout the value chain: reducing product ranges, increasing volumes per reference, pooling collection tools, etc. In this context, support is directed towards consortia of actors that have made efforts towards vertical structuring (e.g. tripartite contracts) and reached critical mass. Under the influence of mainstream retail and multipurpose economic actors, operating in both organic and conventional markets, the European organic specification is relaxed in certain respects. Production techniques developed for conventional farming (e.g. new plant breeding tools) are thus transferred to the organic sector, helping to reduce cost differentials.

This relaxation of standards enables an expansion of conversions. Thus, after the international agreement concluded in 2032, the number of farms and businesses engaged in OF rises again, in a manner similar to the 2000s (see Figure 2). These changes are nevertheless debated, as some actors no longer recognise themselves in this framework. They prefer to establish private initiatives with production benchmarks more ambitious than the new basic organic standard. These concern, in particular, landscape preservation, animal welfare, the stringency of conversion processes, the number of jobs per unit of production, and the distribution of value.

Figure 2 - Evolution of areas, farms and businesses engaged and converting to OF

This graph shows the evolution of certified organic or conversion areas, the number of farms committed to organic farming, and the processing, distribution, and trade companies involved in the organic sector from 2008 to 2023.

Source : Agence Bio, 2024, Les chiffres du bio : panorama 2023.

Reading note: the y-axis shows evolution of OF areas (green), agricultural areas under conversion to OF (orange), number of organic farms (brown) and downstream actors (e.g., retail, processing – blue).

All these trends enable the organic sector to experience renewed growth from 2032 onwards, following a long period of uncertainty (the 2021–2023 crisis) and subsequent stagnation. This redeployment is supported by strong consumption and the maintenance of economic and technical infrastructures made possible by public support: collection and processing facilities, technical expertise within organisations, etc. It is accompanied by a strengthening of supply and demand management, notably through the use of indicators to better monitor sales dynamics. These make it possible to anticipate available volumes on a three-year horizon.

Consumers’ sensitivity to environmental and health issues is high, and scientific discourse on these matters is present in the media. Willingness to pay for organic products increases, as they are perceived as healthy. They are also more visible on supermarket shelves. By 2040, OF is expanding, despite ongoing debates, for example concerning competing specifications. Organic products account for 30% of the food market in France, mainly in household consumption and collective catering.

Scenario 4: Towards Predominantly Organic Farming and Food

Following the multiplication of climate crises and geopolitical tensions, the trend shifts towards deglobalisation. The international community becomes polarised into supranational blocs (European Union (EU), North America, Southeast Asia, etc.), each seeking to strengthen its strategic autonomy. By 2030, environmental awareness advances in Europe, influenced by communication and education efforts, activism in civil society, and the renewed credibility of scientific discourse. Trade focuses on certain manufactured goods and, to avoid excessive environmental or social dumping, the EU redirects its trade exclusively towards countries sharing similar concerns and production standards. At the same time, population ageing and healthcare expenditure increase. Agricultural, environmental and health policies converge towards a “One Health” approach, encompassing human, animal, plant and ecosystem health. In dietary terms, a reduction in calorie intake and meat consumption is promoted. Economically, reducing inequalities is prioritised.

Against this backdrop, non-governmental actors supportive of OF coordinate and launch information campaigns, widely relayed by the media and social networks, aimed at influencing public decision-makers (national authorities, the European Commission, etc.), using well-constructed and impactful messages. OF gradually becomes the benchmark standard for agricultural production, and the French Organic Agency (Agence BIO) increasingly acts as a relay for the new policies. The transition is encouraged by incentives, including financial ones, introduced by the EU. The organic specification becomes the reference framework for the Common Agricultural Policy. Conditionality of subsidies is strengthened in order to reduce agriculture’s impacts on climate (limiting nitrogen fertilisers, practices enhancing carbon storage, reductions in energy consumption, etc.) and biodiversity (reduction of pesticides, agroecological practices, nature-based solutions, etc.). Non-OF systems are permitted, but subsidies are graduated according to the practices implemented. Local authorities fully mobilise the land-use lever: extended pre-emption rights, environmental rural leases, binding environmental obligations, etc. Public support for research, training and technical advice is directed predominantly towards OF.

At the same time, public authorities seek to influence consumption patterns. A food social security scheme is introduced, and a specific tax is created for products with the greatest negative impacts on health and the environment. The EGAlim 5 law imposes a mandatory share of organic products in food retail (25% by 2035). To strengthen consumer buy-in, a new “score” applies to all foods at European level. It is composed of indicators relating to health and nutrition, greenhouse gas emissions, and the preservation of resources (water, soils, biodiversity). In collective catering, public authorities tighten requirements concerning the presence of organic, plant-based and local foods in menus, as well as compliance monitoring. Despite a significant increase in local authority budgets, following extensive debates on food, resources remain uneven, and some flexibility is exercised in the application of national directives (e.g. EU origin rather than local).

By 2040, all actors involved in collecting, marketing and processing develop organic activities. As production volumes increase, economies of scale are achieved and some production costs decline (logistics and processing), although the overall regulatory framework tends to increase production complexity. Specialised actors prosper, their 100% organic positioning giving them strong commercial visibility and a positive image. Some launch private initiatives claiming an “enhanced organic” approach, more ambitious than the new standard and mainstream retail distribution.

The share of food in household budgets rises significantly, reaching 25% on average in 2040, compared with 15% in 2020. Within its “One Health” policy (see Figure 4), the EU requires Member States to guarantee equitable access to quality food for the widest possible population. The Commission proposes the establishment of indicators to verify that disparities between citizens within the same country are diminishing. In France, food and nutrition education from early childhood is reinforced, and substantial food aid is introduced for low-income households.

In steep decline and increasingly unattractive economically, conventional farming nevertheless remains predominant in 2040. The “transition” appears to be a never-ending process. The budgetary resources mobilised are insufficient to support the entire food system. Despite a proliferation of criteria to be met, higher taxation and reduced volumes to be processed, some actors in conventional supply chains (e.g. cooperatives, farmers for whom conversion is difficult) continue to refuse participation in the development of OF. They contest the new political orientations and do not wish to change their production model. Nevertheless, food systems are being reshaped, and the trajectory towards more sustainable agriculture is firmly established.

Conclusion

This foresight exercise conducted by Ceresco and Crédoc was carried out in a singular context, where, after 20 years of almost uninterrupted growth, the entire organic sector is questioning its future. The scenarios developed within the study demonstrate that the issue of a possible marginalisation of organic farming (OF) arises. The consultancies conclude that avenues nevertheless exist to stimulate the organic sector in the future.

In the short term, maintaining a sufficient supply of products in retail and catering for all consumers will be crucial. To this end, support for both intangible infrastructures (human capital, development tools, dedicated funds, governance bodies) and tangible ones (dedicated collection or processing facilities) in the supply chains will be necessary. Price will remain a central factor, particularly for processed products. The image of the organic label will also be of great importance, as consumer choices will likely continue to be shaped by price, brands and the geographical proximity of production. Health-related arguments should also continue to support the development of organic product consumption.

Levers with longer-term effects could also be activated. Accounting for the positive and negative environmental externalities of agricultural practices could in particular improve the competitiveness of OF. The implementation of economic incentives (taxes, financial support, etc.) to internalise these externalities could be facilitated if understanding of agriculture’s environmental impacts extends beyond the circle of already-convinced actors. Environmental education and the visibility of scientific discourse could support this process. Exogenous shocks, such as those mentioned in the different scenarios (climatic hazards, economic or health crises, citizen mobilisations, etc.), could also contribute.

The questions and avenues raised in this study provide a contribution to the reflection on the future of the organic sector in France. They complement other national initiatives, as well as those undertaken in certain EU countries and at European level, such as the Horizon Europe OrganicTargets4EU project. Work based on econometric or biophysical models would allow for the testing and strengthening of some of the hypotheses developed in this exploratory foresight exercise, which was built on the co-construction of scenarios with stakeholders. This work has helped to examine probable developments in the French organic sector and illustrate them through scenarios. It is now up to both public and private actors to build on these elements and support the development of OF.

Bertrand Oudin, Lucas Gouwy - Ceresco

Miguel Rivière, Amandine Hourt3 - Centre for studies and strategic foresight

1 - Céresco, Crédoc, 2025, Étude prospective : quels avenirs pour le secteur bio français d’ici 2040 ?, rapport pour le ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Souveraineté alimentaire

2 - Agence Bio, 2022, Les chiffres du Bio : panorama 2021 ; Agence Bio, 2023, Les chiffres du Bio : panorama 2022 ; Agence Bio, 2024, Les chiffres du Bio : panorama 2023.

3 - At the moment this note was written.

Voir aussi

La segmentation du secteur agroalimentaire français : analyse et tendances - Analyse n° 200

15 mars 2024CEP | Centre d’études et de prospective

Estimation des besoins actuels et futurs de l’agriculture biologique en fertilisants organiques - Analyse n°195

07 septembre 2023CEP | Centre d’études et de prospective

Hétérogénéité des paysages agricoles, biodiversité et services écosystémiques - Analyse n°163

19 mai 2021CEP | Centre d’études et de prospective

Étude prospective sur l’estimation des besoins actuels et futurs de l’agriculture biologique en fertilisants organiques et recommandations en vue de son développement

09 décembre 2022CEP | Centre d’études et de prospective

Mobilisation des filières agricoles en faveur de la transition agro-écologique : état des lieux et perspectives - Analyse n°121

18 juin 2018Recherche, développement et innovation